Tate Britain reappraises James Stirling – who gave his name to Britain's premier architectural prize – and shows he could be good, and bad… but never dull

Potent: Stirling's 1984 Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, Germany. Photograph: Marco Weiss/Alamy

Did the great British architect James Stirling kill architecture in Great Britain? The question has to be asked since, as well as being an original and internationally admired talent, who is sometimes said to be the Francis Bacon of British architecture, he also designed some of the most notoriously malfunctioning buildings of modern times. Worse, two of these buildings were in the ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge, wherein opinion formers spent their formative years. If you want to annoy as much of the establishment as possible, there are few more effective ways than this.

In particular he and his partner James Gowan designed the history faculty and library at Cambridge, completed in 1968. Here, as they struggled to study in this alternately freezing/boiling greenhouse, with dodgy acoustics, frequent leaks and falling cladding tiles, future columnists and editors incubated a deep loathing of the building, of Stirling, and by extension all forms of ambitious modern architecture. In the 1970s the young critic Gavin Stamp made his name with a remorseless hatchet job on the history faculty. In the 1980s it narrowly escaped demolition.

In 1984 the pro-Stirling critic Reyner Banham wrote that "anyone will know who keeps up with the English highbrow weeklies (professional, intellectual or satirical), the only approvable attitude to James Stirling is one of sustained execration and open or veiled accusations of incompetence."

In particular he and his partner James Gowan designed the history faculty and library at Cambridge, completed in 1968. Here, as they struggled to study in this alternately freezing/boiling greenhouse, with dodgy acoustics, frequent leaks and falling cladding tiles, future columnists and editors incubated a deep loathing of the building, of Stirling, and by extension all forms of ambitious modern architecture. In the 1970s the young critic Gavin Stamp made his name with a remorseless hatchet job on the history faculty. In the 1980s it narrowly escaped demolition.

In 1984 the pro-Stirling critic Reyner Banham wrote that "anyone will know who keeps up with the English highbrow weeklies (professional, intellectual or satirical), the only approvable attitude to James Stirling is one of sustained execration and open or veiled accusations of incompetence."

The ‘loathed’ Cambridge history faculty (1968) Photograph: Neil Grant/Alamy Behind most broadsheet tirades against modern architecture in the last 40 years stands the figure of James Stirling. And, when architects are now subjected to the most elaborate forms of control and project management, squeezing out invention in the interests of reducing risk, it is in order to avoid mishaps much like the Cambridge history faculty. Stirling was seen as the very type of the award-winning architect whose buildings don't work. He was, to boot, arrogant, lecherous and sometimes boorish. At a party in the apartment of the New York architect Paul Rudolph, he chose to express himself by urinating against its huge window, from the terrace outside, facing into the crowd of guests.

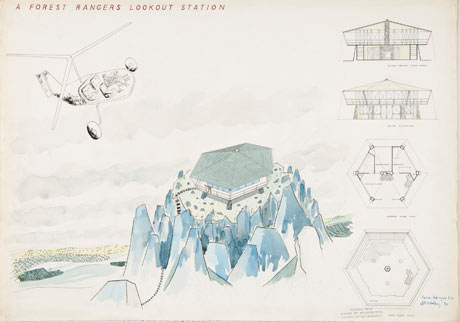

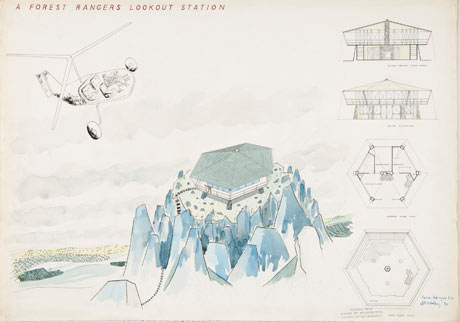

Yet he continues to hold an honoured place. The Stirling prize, inaugurated shortly after his death in 1992, is named after him. Now, as the wheel of fashion grinds inevitably round, his work is up for reappraisal. Next month Tate Britain will honour him with an exhibition based on the impressive archive of his work owned by the Canadian Centre for Architecture. These drawings will reveal him as a more subtle, complex and even charming character. They are skilful, sometimes refined, sometimes informal. Some drawings, composed as presentation pieces after a design was complete, have an abstract elegance. At other times he would cover sheets of writing paper, diary pages and the backs of plane tickets and telegrams with thickets of sketches, as he worked ideas over and over. They might be plans, diagrams or three-dimensional views. They have energy, with much-repeated lines or brisk hatching or Klee-like arrows scurrying through them.

They are signs of thinking with his hands, of trying things out, of exploring and excavating. These are not the disdainful doodles that some architects dash off, hoping that it will be taken as a sign of genius that they can be done so thoughtlessly. They show complete faith that the design of buildings is a serious business, to be pursued with time, testing, consideration and debate. He might try several versions of an elevation, with differences that would not be obvious to a casual observer.

Yet he continues to hold an honoured place. The Stirling prize, inaugurated shortly after his death in 1992, is named after him. Now, as the wheel of fashion grinds inevitably round, his work is up for reappraisal. Next month Tate Britain will honour him with an exhibition based on the impressive archive of his work owned by the Canadian Centre for Architecture. These drawings will reveal him as a more subtle, complex and even charming character. They are skilful, sometimes refined, sometimes informal. Some drawings, composed as presentation pieces after a design was complete, have an abstract elegance. At other times he would cover sheets of writing paper, diary pages and the backs of plane tickets and telegrams with thickets of sketches, as he worked ideas over and over. They might be plans, diagrams or three-dimensional views. They have energy, with much-repeated lines or brisk hatching or Klee-like arrows scurrying through them.

They are signs of thinking with his hands, of trying things out, of exploring and excavating. These are not the disdainful doodles that some architects dash off, hoping that it will be taken as a sign of genius that they can be done so thoughtlessly. They show complete faith that the design of buildings is a serious business, to be pursued with time, testing, consideration and debate. He might try several versions of an elevation, with differences that would not be obvious to a casual observer.

Stirling’s student drawing, Forest Ranger’s Lookout Station, 1949. Photograph: James Stirling/Michael Wilford fonds/CCA They also show faith that architecture is something like music or painting or literature, that it is something to be composed, with tensions and harmonies to be resolved within its overall structure. Stirling kept considering his art in relation to that of others, both 20th-century figures like Le Corbusier and the Russian constructivists, and architects of the Italian renaissance, or the grand industrial architecture of Liverpool, where he grew up. His designs and drawings set up multiple dialogues with other works. And, like artists and writers, he wanted to be provocative. He wanted to wake people up.

These tensions and elaborations, these interplays of forces and allusions, should make it hard to dismiss his work as mere leaky showmanship. His Florey building for Queen's College Oxford is a sort of inhabited viaduct turned into theatrical U-shaped court, a distant derivation of the Oxford quad, facing the river Cherwell. It is Oxonian and constructivist at once. It is perverse but you would have to be a dullard not to see its drama. Students there now comment on its faults but also on the atmosphere generated by this extraordinary hemi-cauldron.

His later work is more likeable and less leaky, as Stirling became slightly less reckless, and as he started building in Germany, where the building industry seemed better equipped to realise his ambitious ideas. His 1984 Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, for example, was one of the biggest tourist attractions in the country, on account of the force of the building. In this it was a prototype of the Guggenheim in Bilbao.

At its centre is a great circular stone court, like an inside-out mausoleum or a new-built ruin, with vines falling down its walls. A system of ramps takes you through the building, as if you were climbing a hillside and, at the moments when it might become too monumental, bright curves of steel and glass lighten the mood. It is romantic, potent and playful at once, and perfectly captures the balance between monumentality and motion, between eternity and perambulation, which is the essence of museums.

The Staatsgalerie wouldn't work without the pushing and pulling of ideas you can see in the drawings. It is worked and wrought in a way few buildings are nowadays. Architects still work hard, and test different ideas, but they search more for a magic formula in the cladding or the form which will make the whole building smoothly beautiful and consistent. There is less sense that a building is composed like a painting, and that the architect should leave some of his sweat and brushmarks on the canvas. Stirling's drawings bring on a nostalgia for a way of designing – among other things, without a computer in sight – that has gone the way of dodos and drafting boards.

Does his art justify the malfunctions? There is, to be sure, more than one side to the argument: Stirling's defenders always said that his projects were victims of poor construction, cost-cutting and clumsy clients. It can also be said that time casts a rosy glow over the faults of more distant architects. The shoddiness of Nash, the impracticality of Vanbrugh and the budget-busting of many great architects in history are now almost forgotten and forgiven. The same will probably happen to Stirling.

Stirling was a very naughty boy. The pleasures of his successes came at an exorbitant cost, not only in technical failures but also artistic ideas that didn't quite come off. The number of his works that are unequivocally admirable are few. Architects are mostly more careful and responsible now, which is mostly a good thing. But, at his best, Stirling showed what powerful and moving things buildings can be, and the world would have been poorer without him.

These tensions and elaborations, these interplays of forces and allusions, should make it hard to dismiss his work as mere leaky showmanship. His Florey building for Queen's College Oxford is a sort of inhabited viaduct turned into theatrical U-shaped court, a distant derivation of the Oxford quad, facing the river Cherwell. It is Oxonian and constructivist at once. It is perverse but you would have to be a dullard not to see its drama. Students there now comment on its faults but also on the atmosphere generated by this extraordinary hemi-cauldron.

His later work is more likeable and less leaky, as Stirling became slightly less reckless, and as he started building in Germany, where the building industry seemed better equipped to realise his ambitious ideas. His 1984 Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, for example, was one of the biggest tourist attractions in the country, on account of the force of the building. In this it was a prototype of the Guggenheim in Bilbao.

At its centre is a great circular stone court, like an inside-out mausoleum or a new-built ruin, with vines falling down its walls. A system of ramps takes you through the building, as if you were climbing a hillside and, at the moments when it might become too monumental, bright curves of steel and glass lighten the mood. It is romantic, potent and playful at once, and perfectly captures the balance between monumentality and motion, between eternity and perambulation, which is the essence of museums.

The Staatsgalerie wouldn't work without the pushing and pulling of ideas you can see in the drawings. It is worked and wrought in a way few buildings are nowadays. Architects still work hard, and test different ideas, but they search more for a magic formula in the cladding or the form which will make the whole building smoothly beautiful and consistent. There is less sense that a building is composed like a painting, and that the architect should leave some of his sweat and brushmarks on the canvas. Stirling's drawings bring on a nostalgia for a way of designing – among other things, without a computer in sight – that has gone the way of dodos and drafting boards.

Does his art justify the malfunctions? There is, to be sure, more than one side to the argument: Stirling's defenders always said that his projects were victims of poor construction, cost-cutting and clumsy clients. It can also be said that time casts a rosy glow over the faults of more distant architects. The shoddiness of Nash, the impracticality of Vanbrugh and the budget-busting of many great architects in history are now almost forgotten and forgiven. The same will probably happen to Stirling.

Stirling was a very naughty boy. The pleasures of his successes came at an exorbitant cost, not only in technical failures but also artistic ideas that didn't quite come off. The number of his works that are unequivocally admirable are few. Architects are mostly more careful and responsible now, which is mostly a good thing. But, at his best, Stirling showed what powerful and moving things buildings can be, and the world would have been poorer without him.